Googling David

(ORIGINAL-LENGTH VERSION)

by Bill Zarchy

|

| David and Bill at Buckingham Palace after the Changing of the Guard |

I like to google people from my past. I never know what I’ll find. Once I googled Mr. Tavis, my elementary school principal, a huge man with a booming voice, and discovered that he had sung on Broadway in the late 40s. A month ago I googled Nancy, a producer with whom I had worked extensively at Channel 2 in Oakland in the late 70s. I located her working as a teacher and journalist in Denmark and soon initiated a flurry of emails. That same week, I googled Kevin, a former marketing manager for Sony and Ampex whom I hadn’t seen for 15 years. I found him living in Beijing, selling broadcast equipment, and about to hop a plane to an industry convention in Las Vegas I was planning to attend. We conspired to meet for lunch. Last week, I googled David Sigelman ‘68, my Dartmouth roommate. I found his name on websites for his pediatric practice, teaching awards, a community music center, a book group he started, an article he wrote on prescription drugs and the FDA, and an ominous three-day-old link from a newspaper that included the words, “he was working in a clinic in Peru and became ill. I adored David Sigelman…” I followed the link and was horrified to learn that David had died suddenly, less than a week before, during an altruistic health care trip to the remote Andes. Until just recently, I hadn’t seen David in decades. He grew up in one of a handful of Jewish families in Watertown, South Dakota (“15,000 Friendly Folks!”), viewed our surroundings at Dartmouth with a sense of awe, and projected a charming, self-effacing sweetness. He approached his studies with determination and worked his butt off, eventually graduating with honors. I was a suburban New York Bar Mitzvah boy who viewed the Ivy League, a bit arrogantly, with a sense of entitlement. Indeed, I had been groomed for years for Princeton by my cousin Ted, an avid alum. Ultimately Princeton didn’t admit me, but Dartmouth beckoned. I’d coasted through high school with A’s, and I drifted through college with C’s, as the Vietnam War roared by outside. David and I pledged to different fraternities—Tau Epsilon Phi for him and Foley House for me—but we lived together for two years. Freshman year we lived in South Wigwam Hall, later renamed French. Our sophomore year, we shared a large room in Cutter Hall with a visiting Swedish student named Tomas Bertelman, an accomplished linguist. We made plans to move into a spacious room in Russell Sage for junior year, but I was offered a rare, coveted single room in a suite in Little Hall with another group, so I changed plans. David and I remained friends, but unfortunately we saw each other much less. Towards the end of our senior year in 1968, my parents offered to send me on a summer trip to Europe. David and Tomas had been planning a road trip across the Continent and graciously let me tag along. David had previously done community work in Mexico, but I had never left the country before, except for a two-day family trip to Quebec when I was ten. My two roommates met in Sweden and drove through Eastern Europe in Tomas’s mother’s red Austin Mini Mark II. They particularly enjoyed visiting Prague during the Czech Summer, a short-lived flourishing of art, freedom of expression, and culture during a thaw in Soviet domination that ended tragically later that summer. I flew to London for a few days, then on to Vienna, where we rendezvoused. The three of us crammed into the red Mini and burned up the road across southern Europe, staying mostly in small, fleabag hotels. We dallied three weeks in Spain, as Tomas was studying for a Spanish exam at the end of the summer. We gaped at Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, and mellowed at the Alhambra in Granada. On a beautiful Andalusian road in southern Spain one day, we passed an imposing figure, an officer of the feared Guardia Civil in dark glasses, triangular hat, and black hip boots, standing next to his motorcycle and glaring at traffic. A few miles later, after pulling over for a picnic lunch, we were startled to hear the motorcycle of the Guardia officer. He stopped across the road to watch the cars, then noticed us, hopped back on his bike, and squirted across traffic. As David and I watched openmouthed, he strode over to Tomas, pulled out a knife, extended his hand, and said a few words. The Swede, who had been peeling an orange with difficulty, handed it over, and the officer demonstrated how to remove the peel in one continuous, spiraling cut. He soon roared away to intimidate more drivers. “What did he say to you?” I asked Tomas later. “He said it’s much easier to cut in one piece if you use a sharp knife." |

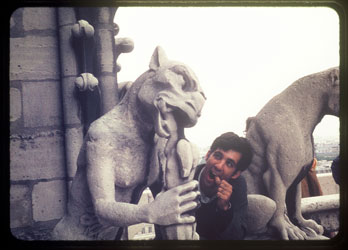

David clowns around

with a gargoyle after climbing to the tower of Notre Dame in Paris Tomas, Bill, and David

under the huge bronze horses on the balcony of the Doge's Palace

in

Venice (thumb courtesy of a helpful tourist-photographer) Tomas and David at

the Rodin Museum in Paris

Toward the end of July, we zoomed north, and Tomas dropped us in France, then dashed home to Göteborg. David and I spent a week in Paris and took a day trip on the train to Chartres Cathedral, where the English language tour guide captured our attention. A young Brit named Miller, he knew every sculpture and stained glass window and changed the focus of each tour, twice a day. David and I speculated privately about Miller, wondering why someone so brilliant would get “stuck” there in that small town. In those days before the Euro and the Chunnel train, Chartres seemed like a backwater to us, such suave, Ivy League men of the world. We trained to Amsterdam, rented a room from an older German woman who approached us at the station, and stayed up late chatting with her and her Italian tenant about World War II and Vietnam, aided by my high school German and David’s fluent Spanish. We flew to Edinburgh, traipsed around Scotland for a couple of days, and decided to hitchhike to London. No one would pick us up. Young people with Czech flags would get rides in moments, but we waited at one truck stop in the Midlands for hours. “We look like gringos,” said David, even without a USA sign or flag. Passing drivers, presumably angry about Vietnam, responded to our thumbs by waving other digits. Canadian hitchhikers vigorously maple-leafed passing vehicles to distinguish themselves from us. Then our luck changed: a kindly lorry driver named Graeme picked us up and eventually took us home to his girlfriend and a large apartment in Birmingham, where they made us welcome for a few days. Back in London, David and I flew home separately, both permanently bitten by the travel bug. I endured severe culture shock, returning to the States the day Chicago police tear-gassed student demonstrators at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. That same month, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia, crushing the brief explosion of freedom. David and I saw each other once or twice the next year, while he studied at Dartmouth Medical School and I taught high school social studies in a small Vermont town. But after that, I lost track of him for a while. I attended our tenth reunion and was disappointed not to find him there. I remembered his Dad’s name and wrote to David at his parents’ address in Watertown. I told him about going to film school at Stanford, my years starting out in film and television in California, a recent trip to Japan with Fleetwood Mac, my engagement. He wrote back, told me he was specializing in pediatrics and settling in Massachusetts, that he didn’t attend the reunion because he was embarrassed at having been such a “greasy grind” in college—something between a devoted student and a party pooper—though I assured him my image of him was different. He didn’t go to our 25th reunion, either, but a mutual friend who had seen him recently filled me in. David was living in Western Massachusetts, partner in a well-established pediatric practice, married, teaching, doing community work, raising a family. And, said the friend, David had learned to play the viola da gamba, like Gerard Depardieu in the recent French film “All The Mornings of the World.” Oddly, I still felt close to David, even after so many years. Inspired by his example of picking up an instrument later in life, I soon began studying the guitar. For inspiration, I sometimes visualized a montage of David and Depardieu playing the viola. The night before my departure for our 30th reunion in June 1998, at my son’s Little League dinner near my home in California, I sat next to a local pediatrician, father of another player. Serendipitously, he turned out to have been great friends with David in medical school. He gave me David’s office number in Holyoke, and I called the next day and left a long message, trying to convince him, at the last minute, to meet me at the reunion. Later that day, he called me on my cell phone, and we talked for half an hour while I changed planes in New York. He might have been tempted to come, he said, but that weekend he had plans to meet his family in Florida, where his Mom had retired. We promised to stay in touch and exchanged email addresses. Later that summer I was in France with my wife and kids, where I noticed in a guidebook that Mr. Miller still led the English tours at Chartres Cathedral. I dragged my family there. Chartres was a medium-sized city, I realized as we arrived on the train, and I wondered if it had ever been a small town in my lifetime. The cathedral, deservedly, was a Major Pilgrimage Destination, Miller a world-renowned author and expert. “Has any of you ever taken my tours before?” asked Miller as we basked in his brilliance with the other tourists. Hands went up. “How long ago, sir?” “This morning,” answered a man. “Five years ago,” said someone else. “Thirty years ago this month!” I cried out, recalling our erroneous assessment of Miller and his “backwater.” I bought two Chartres guidebooks, one to keep and one to send to David with an account of my return. When we got home, I put them both in a bookcase in my office. Just a few months ago, I got an email from David, telling me he would soon visit San Francisco for a public health convention. We met for dinner and spent hours catching up at a French bistro on South Park. Except for some graying at the temples, he looked the same as he had in college. He was delightful to be with, slim and fit, alert and energetic, with a maturity, poise and confidence that I had just seen hints of during our college days. He described his trek in the Himalayas with his wife Pat and flabbergasted me with the news that Tomas had served as Swedish envoy to several countries (I recalled the incident when the Guardia officer showed the future ambassador to Spain how to peel an orange). We talked about our families—both of David’s parents had passed away by then, and I’d lost my dad a little over a year before. We’d both loved being daddies, and he told me how difficult it had been for him when his “younger offspring” had moved out, the nest finally emptied, an event I was anticipating—and dreading. He shared his pride in being part of a pediatric practice that served a culturally and economically diverse population. |

David peeks through

the sculpture in the garden of the Rodin Museum in Paris Tomas at a cafe in Piazza

San Marco, Venice Bill relaxes at the

same cafe

He described his volunteer trips to Peru as a reaction to the emptiness after his kids were gone. He was planning a third journey to the remote Altiplano region of the Andes, to small, impoverished villages at 11,000 feet and higher, where he worked with other doctors from Bay State Medical Center to provide pediatric care and train health care workers. In addition, he had established a program, Project INCA, to help the villagers build simple greenhouses to combat severe malnutrition in the area. I told him about my travels and my writing, described seeing Miller at Chartres again, and promised to send the picture book I’d bought for him five years before. Remarkably, we spent the evening catching up on our histories and passions, not reminiscing about college. Later we went to a club in the Mission District to meet his son Ben, recently hired on at Google, the search engine company in Silicon Valley. We hung there for an hour or so, then hugged goodbye. We hoped to see each other more, since he’d be coming out regularly to visit his son. I wrote to him the next day, noting that we still seemed to know each other well, no doubt from bonding during an ordeal “driving the porcelain bus,” after a near-fatal overdose of vodka and grapefruit juice in the fall of our freshman year. “I was touched by your pointing out that our parents were the ones to whom we could puff out our chests with pride re: our own accomplishments or the accomplishments of our offspring… “And yet, there we were last night, puffing out our chests and extolling our various kids to each other,” I wrote. “So maybe it’s okay to do that with old friends as well…” * * * Ironically, the day David died, I was celebrating life with my wife and children at my mother’s 90th birthday party near Phoenix. It had already stacked up as a momentous and heartbreaking day: my kids had to choose between coming to Arizona for my mom’s party and attending the funeral of their friend—a young man who had just died of leukemia—in the Bay Area. To discover that David had died on the same day was terribly sad. Preliminary indications suggested his death was caused by a pulmonary edema brought on when David and a companion climbed to 15,000 feet in the Andes. I was shocked and upset at the news and refused to believe it, until I found a memorial page for David and an article from a newspaper in Springfield, Mass.: “Beloved Doctor Dies…” “He was the rare type of doctor, one that you just do not find today,” wrote one reader to the newspaper. “He had a passion for what he did and he did it well. He was a class act and will be missed by so many children and parents.” A memorial fund to continue David’s community work locally and globally has been established in his name withthe Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts. In a hall packed to overflowing on the Smith College campus, nearly 1000 friends, neighbors, colleagues, patients, students, and musicians paid tribute to David at a moving memorial service. He was 58, and leaves his wife Pat McDonagh, daughter Katie, and son Ben. I never know what I’ll find when I google someone from my past. I’m grateful I had the opportunity to reconnect with David, however briefly, that I was able to see him in his prime, to see how the modest South Dakotan had turned out, to tell him a bit about my world. After three decades apart, we had three or four splendid, rewarding hours together. It felt like a bonus at the time. I thought that we might have more dinners and get to know each other’s families, that our friendship had more of a future. But the Chartres book is still in my bookcase. I thought we had plenty of time. |

|

David checks out election posters on a wall in Spain |

|

|

|

Tomas cools off in a fountain at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain |

|

Tomas poses before a mosaic wall, somewhere in Spain |

|

|

|

Tomas and David in Venice |

Europe '68 photos by Bill Zarchy, David Sigelman, Tomas Bertelman, and passing tourists

|